Learn Hanja the Fun Way!

After my post (When Goggle was Gobble-Dee-Gook) describing some of the developments that have taken place in the last ten years which now provide greater support for those interested in Korea and Korean culture, a post on a book on hanja designed specifically for the non-Korean student.

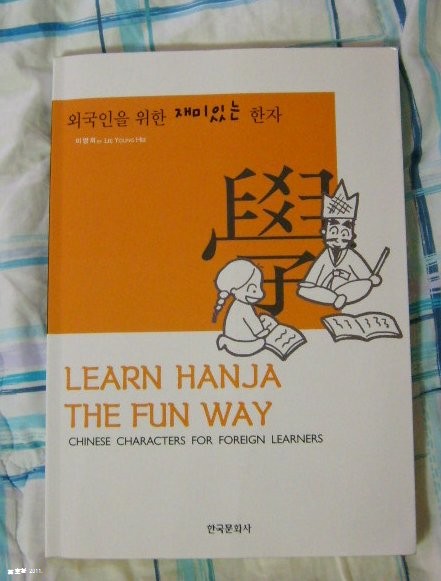

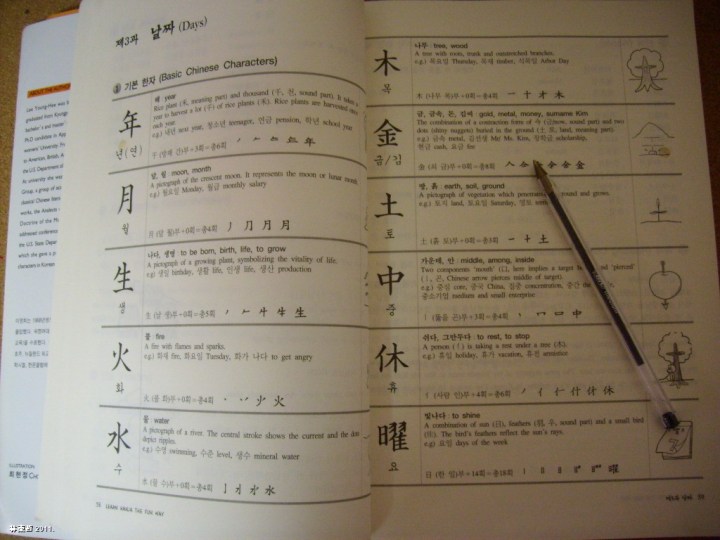

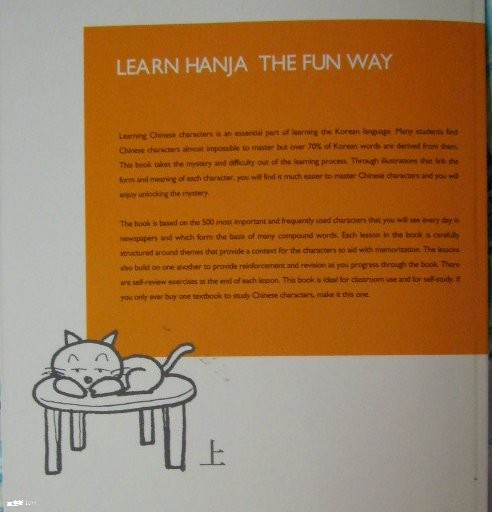

Learn Hanja the Fun Way, by Lee Yong Hee is extremely user-friendly and presented in a manner that introduces the student to the major radicals and links them to their pictographical roots. The remainder, and bulk of the book is focused on 50 theme based lessons covering topics such as numbers, days, people, the family through to the economy, university and globalization. At the end of each topic a passage is provided in Hangul which incorporates the hanja characters presented up to this point. The reading comprehension is of great benefit as it helps consolidate learning and provides an example of how hanja is used. The author has taken great care to ensure the Hangul isn’t too difficult to present yet another problem. Each topic is rounded of with a four character proverb from the famous Ch’on Cha Mwun, One Thousand Characters (천자문). At the end of the book is a useful section providing hanja for country names, Korean cities, surnames and antonyms.

This is the first book I have seen which is designed specifically with the non-Korean speaker in mind and along with Bruce K Grants, A Guide to Korean Characters, will allow you to master the 1800 characters used in South Korea. All you need now is 20 years of study!

Learn Hanja the Fun Way (Chinese Characters for Foreign Learners), by Lee Young Hee (이영회), is available in most large book stores. I bought mine in Kyobo Books, Daegu. It costs 14000 Won and is published by Hangookmunhwa Sa (한국문화사). ISBN 978-89-5726-232-0 13710.

Homepage: hankookmunhwasa.co.kr

© 林東哲 2011 Creative Commons Licence.

In the Days When Google was Gobble-dee-gook

I often mention that ten only a few years ago there was little information available on most aspects of Korean culture. Looking back just a few years the changes that have taken place are truly incredible. For those of us who are older, it is easy to forget that access to a whole range of information, all at your fingertips, is a luxury that at one time did not exist and that ‘one time’ was only a couple of years ago; for those who are younger, it is worth pondering the Korean experience before the incredible growth in access to, and compilation of, information – a process still in development.

When I decided to come to Korea in 2000, it certainly wasn’t for a job and the only factor influencing my decision to step on the plane was to discover a country which at the time ranked with exotic and mysterious destinations such as Mongolia and Tibet. Just ten years ago anyone coming to Korea, perhaps more so from Europe than the USA, which has had both a closer relationship with Korea and attracted a substantial number of Korean immigrants, did so blind. Other than the information supplied by your recruiter and the odd book in libraries, access to information or first hand accounts was scant. Those who decide to come to Korea today are able to furnish themselves from the abundance of information available in a range of formats and I suspect many are now lured here not because of the mysterious, but in search of employment. I in no way mean to demean or underplay the reasons people currently come to Korea and it certainly provides a culture shock. But I envy those who arrived here in the early 1990’s or 1980’s at a time when Korea was not the place it was in 2000.

I kept a diary from my first day and reading through its pages it is clear how the internet has become a fundamental resource in both deliberating whether to undertake the experience and in influencing and developing your understanding of Korea. It may even influence the experiences you engage in while on the peninsula. Change has been so rapid, and the resources we now access have become so integral, it is easy not just to take fore-granted its impact, but to even doubt that it was really that difficult to access information in the first place.

Writing in hangul was a major obstacle and you simply couldn’t go into your PC, make a few tweaks and then be able to write in Korean or hanja and besides, in 2000, few teachers had air-conditioning let alone a personal computer with an internet connection. Before laptops and net-books, most of the waygukin you met were in PC bangs where you spent a substantial part of your week. And If you bought a PC you were privileged but still required Microsoft Proofing Tools to enable you to write in Korean or hanja and which cost c£70 a package.

Korean dictionaries, certainly in the UK, were small and difficult to buy. On the eve of my first trip, I went to London’s largest bookshop, Foyles, and discovered the entire range of books on the Korean language amounted to two introductory books, a useless dictionary and the small copy of the NTC Compact Korean English Dictionary. I bought all four depleting them of their entire Korean language collection. The dictionaries used transliterated Korean rather than hangul script. Meanwhile, books devoted to Japanese occupied an entire book case.

I’ve known a number of westerners who arrived in Korea in the late 80’s and whose Korean, many years later, is still rudimentary. It’s easy to criticise such apparent laziness until you remember there was no internet to support your learning or provide lessons, few decent language courses or dictionaries and unless you were in Seoul or one of the big cities, few language classes. After a few years enduring such conditions it becomes a case of, ‘you can’t teach an old dog new tricks.’ As for hanja, I’ve met westerners proficient in Korean who didn’t even know what hanja was. While access to information on the internet existed, certainly around 2000, there was very little compiled on Korea or Korean culture and the ability to write in hanja characters was difficult, costly and dependent on Korean based language packages. Today, though limited for the non Korean speaker, information on hanja is available and if you aren’t interested in trying to learning it, you can very easily research what it comprises.

Once again, in the UK, other than on the Korean war, there were few books on Korean history and finding information on topics such as the Hwa-Rang-Do or one of the Korean dynasties, was difficult. And when you did find such books, usually in academic libraries rather than public ones, they were specialist and somewhat boring for the reader who wanted general information. It has only been in very recent years, by which I mean the last 6 or 7 that such information has appeared and I can remember trawling Google in 2002 or 2003 and finding very little other than specialist academic references to major, Korean historical periods. Exactly the same conditions applied to Korean culture, prominent figures, cooking or geography. Back in the UK I have a small collection of books on Korean culture, history, cooking, hanja and language etc, but all of them were printed and bought in Korea, and ferried back to the UK. So, on returning to Britain in 2002 and 2004, I felt I had to take a part of Korea home with me because there was no way to access ‘Korea’ in the UK. In 1997, when TOPIK, the Korean language proficiency test was introduced for non-Korean speakers, it attracted 2274 people; in 2009, 180.000 people took the exam and test centers now exist globally.

Korean related information on the internet was in its infancy; Google, for example, became a registered domain name in 1997 and certainly before 2000 most lay-people researched information from software such as Encarta. In 2000, I was originally going to teach in Illsan, I can remember using the internet to find information on this location and found very little. I have just this moment keyed ‘Illsan’ into Google search and in 14 seconds have access to 1.800.000 written resources and 1200 images. Learning Korean and hanja meant you compiled your own dictionary because the words or characters your learnt weren’t in dictionaries and there were no translation tools such as Babblefish or Google to provide support. Even with hangul, I still keep my own dictionary because western ones, even on the internet, don’t explain words uniquely Korean. As for idioms? Try searching Korea idioms on the internet or the availability of electronic dictionaries which are designed for the English native speaker learning Korean. All resources still being developed.

Resources in their infancy 10 years ago, blogging, vlogging, podcast, Youtube, Facebook and Twitter etc, have since become a fundamental means of sharing experiences and providing first hand information not just about all aspects of Korean culture, but on more specific topics such as life for the foreigner and whether you are vegetarian, teacher or gay, information is readily available. Blogging now provides an immense wealth of information but it is worth remembering that the term ‘blog’ was only coined by Peter Merholz, in 1999. Major blogging software which has helped give rise to the blogging phenomena are recent developments: Blogger emerged in 1999 and WordPress in only in 2003.

Even today, unless you live in London, obtaining Korean foodstuff is still almost an impossibility and online order of Korean foodstuffs is undeveloped. None of this is very surprising given there were very few Korean living in the UK until recently. Between 1998-1992, at a university with one of the most diverse students populations in the UK, there was a total absence of Koreans and Russians. Indeed, I was to meet Mongolian students before I met any from Korea. And, I can recall the very first five Korean I met; the first, a taekwondo instructor in London, in 1979, the second, a taekwondo instructor in Paderborn, Germany, in 1986, the third, a student in a school near New Maldon, London, in 1998, and finally, two Koreans in a hotel in the Philippines, in 1998. I had a fleeting ‘meeting’ with Rhee Ki-ha (now 9th Degree Black Belt, taekwon-do), in 1988 but as a grading taekwon-do student, I was forbidden to talk to him.

Korean Culture – the Korean Wave, Korean football players playing for British football teams, LG, Nong Shim, I-River etc, all arrived on British shores in the years following my first visit and indeed, this Christmas, I was treated to the first Korean cookery program I have see on British television. However, I suspect its genuineness as the recipes included beetroot and English pear (you can easily buy Asian pear in the UK). And neither chopsticks or kimchi featured!

Up until a few years ago, if you arrived in Korea from Britain, you probably knew nothing about Korean society and possibly expected ‘second world’ conditions. Much of what you learnt about Korea occurred through accidentally stumbling across something and you certainly couldn’t learn from a computer screen. Indeed, access to a computer was probably detrimental to your Korean experience, removing you from, rather than immersing you in, Korean culture. Today, a computer can certainly enhance your experience and if you need to know how to: use your Korean washing machine, plan a trip, find a doctor during a holiday or translate a sentence from Korean into Blackfoot, it’s at your fingertips. Day to day life in Korea has been ‘made simple’ by the tomes of information we can now access and only last week I used the internet to help me adjust my ondol heating control. With hundreds of accounts on topics such as soju, the Boryeonng Mud Festival and kimchi, done to death, a blogger is forced to use a range of media formats (vlogging, photographs, podcasts, even cartoons), and driven to be more creative and original in their perspective especially if posting on what are now common, if not mundane subjects.

Link to TOPIK Guide.

© 林東哲 2011 Creative Commons Licence.

Would You Believe it – Mushroom Wine!

Traditional mushroom wine might not sound very appealing but at less than 2000 Won (£1) a bottle, it’s worth a whirl. Actually, over the past three months I’ve been meaning to write this post, the bottles I’ve bought to photograph and sample, I’ve ended up drinking which is testament to the fact it can’t be that bad, especially considering I’m not much of a drinker.

The aroma is a combination of wine with a lurking invisible mushroom, which is pretty much what you might expect. Developing a taste for this wine probably lies in forgetting the main ingredient is mushroom as pondering on the taste can only evoke references to moldy bread and mushroom soup none of which do the drink any justice. Once you can put such associations aside, it develops its own appeal. At 13% alcohol content, it is comparable to stronger European wines but is sweet, though not excessively, rather than dry. I am not a wine connoisseur, and suspect a true wine buff might find it revolting but it seems to grow on you without requiring you to be pissed in order to do so.

I don’t know if there are many types of Korean mushroom wine, as most places I have tried only have pine mushroom wine (송이 버섯). The pine mushroom, known is Japan where it is prized as the matsutake (tricholoma matsutake) is fairly common in Korea and grows under duff in pine forests though the mushroom has symbiotic relationships with various other species of tree.

The company Yangyang Minsok Doga, make an interesting variation using the pine mushroom and ‘deep sea water’ though the bottle looks more like a mineral water and I’m not sure what comprises ‘deep sea water.’

I’ve also discovered a splash or two makes an excellent addition to kalbi-tang (rib soup) and am wondering what other cooking uses I can put it to: sauteing meat or used as base to boil mussels?

© 林東哲 2011 Creative Commons Licence.

Death Could Hardly Taste Fresher – Smelts (빙어)

Last night, on my way home from school, I noticed the smelt van pulled up on the side of the busy cross road which I use several times a day. Every few months this small van appears and it’s always noticeable, perhaps more so for the waygukin (foreigner) because of its strangeness. Patches of snow and ice, from the recent nuclear winter, lay on the sidewalk and the air had an invigorating nip. From the smelt van interior steam, illuminated by the little bright lights around the van, intermittently billow out into the evening air, wafted away by puffs of chilly wind. On the back of the van sits an enormous aquarium on which a couple of small lights focus and the light, refracted from the furthest glass panel, makes it appear as if you are looking horizontally into a vast expanse of blue water in which a thousand small silver fish frantically swim like slivers of glass.

Koreans call them bing-oh (빙어) and they one of the less common streets foods whose western name, smelts, has a rather ironic foreboding. Smelts are the name for a family (Osmeridae) of fish (probably the hypomesus japonicus) which inhabit the water between Korea and Japan and which swim in large shoals. Various species of smelt exist both in the major seas, oceans and in freshwater but the Korean specie is one of the smallest, only a few centimeters long. Stood watching them is mesmerizing and it’s easy to see the therapeutic use aquariums have as a means of inducing relaxation and lowering blood pressure; a couple of seats in front of the tank would surely attract customers.

However, the hypnotic lull into which you might be drawn is shattered when a large sieve suddenly invades the watery expanse and scoops up a few hundred unfortunate smelt, quickly folds them in batter before immersing their twisting bodies in the scorching oil of the deep fat fryer in which they instantly expire amidst spitting fat and a sigh of steam. From a vibrant alive to a crispy, and rather tasty, cooked and dead, in less than two minutes.

The smelt van is a holocaust on wheels and it doesn’t do to ponder too long on how a fish might perceive the various processes practiced. Being tossed in batter and chucked in the fryer is a fairly horrible way to go. However, the smell of fried fish quickly rescues one from contemplation and their tasty crunch has the capacity to banish both empathy and sympathy. You have to eat tempura at the cooking source because by the time you get home the batter is cold and soggy but eating those delicious little morsels under the van’s canopy reminds me of how little respect we have for fish. Imagine a van with a small chicken pen perched on its tail, the chickens contentedly pecking away at grains of corn strewn over the pen’s grass floor. And then, a hand grabs a chicken, chops off its head and expertly plucks the feathers and while still in the throes of death, drags it through some batter before committing it to the fryer. No tantalizing aromas could banish my horror nor the tastiest, succulent flesh extinguish guilt. With warm blooded animals, even a stupid chicken, the point and location of death and the culinary process have to be clearly separated. Many of us are so mortified by warm blooded death that we can’t even buy the flesh in the same location in which it was killed and in the English language have to partition the meat for the animal; personally, ‘pork’ is infinitely more palatable than ‘pig’ and a lot less likely to incur pangs of guilt. At least Koreans appear less troubled by canivourism when they are able to suck on a pork bone in a restaurant in which the walls or menu are adorned with photos, paintings or other images of piggies, in some cases bizarrely anthropomorhphised.

But I can quite easily enjoy a mouthful of bing-oh while watching them swimming about and romaticise that puff of steam which is lifted into the city’s air as each batch is annihilated. Few, if any animal right exist for the bing-oh or indeed most other types of fish and able to watch the entire process from fish to food, with no remorse, I am aware of not only how callous I am, but how smelted in the deep fat fryer, death could hardly taste fresher!

© 林東哲 2011 Creative Commons Licence.

More Tips on Cabbage Kimchi

I am now quite proud of my cabbage kimchi, a skill which has taken me about ten years to get right. One reason why it takes a long time to make decent kimchi is that you have to develop a sense of what constitutes a good kimchi and an awareness of kimchi at different stages of fermentation. Unless you have a cultivated appreciation of what Kimchi is, and by that I mean an awareness of kimchi that a Korean would enjoy and not what you personally think it should taste like, your kimchi will never be authentic. The subtleties of kimchi are as intricate and extensive as wine or Indian curry and an appreciation is important if you are to use a recipe to guide you.

There exist many recipes for cabbage kimchi, regional, personal and for accompanying certain meals; bo-ssam (boiled, sliced pork, 보쌈) for example, uses a special type of kimchi. I am concerned here with the standard type of kimchi that accompanies the majority of Korean foods and which can be divided into two categories, fresh and sour. There is of course, a range of flavours in between these extremes. Many Koreans have a preference for one or the other and foods which use kimchi as a major constituent, as for example with kimchi stew (김치 찌개 or 김치찜), suit one or the other.

I’m told by Korean friends that big cabbages are not the best to use and that medium sized ones, which compared to Britain are enormous, are the most suitable. The outer leaves are trimmed and unless damaged these shouldn’t be thrown away as they can be used in other recipes.

One of the most persistent problems I faced was the most crucial; namely getting the salting process right. Even cook books sometimes overlook what is a seemingly simple procedure. When the prepared cabbages are ready to paste with your kimchi paste mix, they should resemble a dishcloth by which I mean they should be floppy and it should be possible to wring them without them tearing. If you get your kimchi paste wrong you can always adjust it. Even if you subsequently discover your kimchi is too salty it will mellow as it ferments but should the kimchi fail to wilt properly it will not be easily rescued.

Many recipes gloss over the salting process and only this week I read Jennifer Barclay’s book, Meeting Mr Kim (Summersdale, 1988). The book is an interesting account of life in Korea and not a cookbook, but her kimchi recipe, and she is not alone, simply directed you to soak the cabbages in salted water. If as recipe does not explain the salting process in some detail, tread with caution! I once used an entire big bag of table salt in which I soaked the cabbages for several days and they still failed to wilt effectively. The salting process is actually simple if you use a coarse type of salt (such as sea salt or if in Korea 굵은 소금)) and sprinkled between the leaves is all that is required to wilt the leaves in several hours, depending on room temperature. When I make kimchi in the UK, I am forced to use cabbages which are almost white in colour, very stemmy, and which are too small to quarter but even these wilt if treated properly. After salting the washed and wet cabbages they can be placed in a bowl or sink, sprinkled with extra salt and a few cups of extra water and left. Immersing them in water isn’t necessary. In hot weather the wilting process is much quicker. You should notice the cabbages almost half in volume and soon become limp, floppy and wringable.

- Like rice, traditionally, Koreans rinse the cabbage three times. I have learnt it is much better to rinse them thoroughly, perhaps removing too much salt but this can always be remedied later. However, if you use the correct ammount of salt and don’t sprinkle excess on, three rinses are adequate. You can feel where salt residue remains as the stems are slimy and you can remove these by simply rubbing your fingers over them.

Salty kimchi will mellow with fermentation, it is probably better for it to be not salty enough than too salty, especially given the concerns over salt and blood pressure. One hint Mangchi suggests is adding some thin slices of mooli (무) if it is overly salty.

A good kimchi paste will cling to the leaves like a sauce so it is prudent to drain the segments and even wring water out and this will prevent your kimchi becoming watery as the cabbages ferment.

Plenty of recipes, online and in books, will guide you through making the paste but my all time favourite is Maangchi. Her website is enormous and her videos on Korean cooking are well presented. Here you will also find other ways to use kimchi as well as many other types of kimchi, cabbage and otherwise.

British friends who have since become lovers of kimchi often ask me how long it will keep. I tend to keep kimchi in the refrigerator in hot weather and somewhere cold, but not freezing, in winter. If you like kimchi fresh (newly made,) keeping it cool or cold will delay fermentation. If you like it sour then you can use a warm place to speed up the process. I tend to juggle things in order to better control fermentation. I made my last batch of kimchi in November and the tub in which it is stored has stood on my balcony almost 6 months. I have now moved it to the bottom of my fridge to mellow indefinitely. I have used kimchi that was over 6 months old and which had white mold on the top but this washed off and the underlying cabbage was excellent as the basis for a stew.

For my up to date and effective Kimchi recipe, check the, My Recipes, page.

©Amongst Other Things – 努江虎 – 노강호 2012 Creative Commons Licence.

I Would Have Played Hooky But…

I woke this morning (Monday) to find Daegu covered in snow; and heavy clouds, typical of the ones that exist much of the year in the UK, hugging the tops of nearby apartment buildings. The clouds are gray and that they are pregnant with snow is forecast by the fact they are tinged yellow. There is a bitter wind that nips the extremities and all around large snow flakes, whipped by whirls of wind fall crazily. The flakes are so soft, delicate and light that they accumulate thickly on the branches of nearby pine trees. I would love this kind of day in the UK, the perfect conditions for phoning in sick if you live within walking distance of work, or if you use public transport or car, then by exaggerating how bad travel conditions are. Neither would there be a need to use one of the trump-card, ‘sicky’ excuses, such as having diarrhoea or cancer; ‘excuses’ which are perfect for terminating any form of interrogation. Of course, a cancer excuse demands further action as it doesn’t just go away and colleagues would expect further developments, unless it’s posed as a ‘scare,’ in which case you can script yourself ‘all clear.’ Neither is it likely to do you any favours if your ploy is foiled.

Most people would spare a chuckle for the colleague feigning a cold, flu or diarrhoea but a cancer feign is taking too far and is definitely likely to backfire, if discovered. ‘Diarrhoea’ however, is a great excuse because at 7 am and half way through their egg, bacon and brown sauce, no boss is going to start quizzing the causes or manifestation of your condition. If your boss is a bit of a twat, a few references to how runny your condition is or how you never quite made it out of bed on time, will quickly see them eager to terminate the call while simultaneously offering you the speediest recovery. And next, with an authorized day pass, it would be a trip to the local corner shop, braving the conditions en-route that prevent you from getting to work, for a few bars of chocolate, or whatever comfort food takes your fancy. Then, once back home, it’s off to bed accompanied by a hot-water bottle and a couple of good movies.

It’s amazing how utterly relaxing and enjoyable a ‘mental health day’ is when taken in someone else’s time. You can never get the right feel if you take one at a weekend or during a holiday because guilt at your laziness gnaws your conscience and in any case, the weather is rarely suitable. ‘Sickies’ in summer lack the potential to pamper and fail to provide that cosy snugness and if you have a house or garden there’s always something else you should be doing. Climatic conditions which drive you indoors and force you to seek the warmth of your bed or duvet, the sort of weather which typifies disaster movies, are prerequisite for a rewarding ‘sicky’ and they are even better accompanied by a suitable climatic disaster movie involving nuclear winters or avalanches. And there’s absolutely no guilt because conditions are so shit you wouldn’t be doing anything in the garden anyway! But the ultimate ‘sicky,’ one which unless you are cursed with the protestant work ethic, provides a taste of heaven, is one which is taken both at somebody else’s expense and during bad weather when the only thing you would be doing, is working.

In the UK, a flurry of snow is enough to cause trains and buses to cease and you can guarantee that once public transport has shut shop, half the population will be phoning in with colds or flu or excuses about being ice-bound. The merest dusting of anything more than frost and my niece and nephew are begging to be excused school and their front room looks directly onto their school facade. You can’t blame them as in recent years the example of the rich and powerful are ones predominantly inspired by decadence and self-interest.

When I was a teacher in the UK, I probably averaged 10 ‘sick’ days a year, even if I was on a part-time contract. Sometimes they were taken because I had better things to do than work – things such as taking an exam or a driving test. More likely, they were because I was simply stressed and found it difficult to amass the energy to teach a bunch of kids who usually had little interest in learning. I would have few allegiances to a school in the UK, certainly not as a chalk-front teacher in a run of the mill school (as most are even though they all claim the opposite), and consider teaching a form of prostitution. Indeed, I’ve known teaching friends incite the scummiest pupil they knew until enraged, they attacked them. Strange, how even though the attacks were minor, sometimes involving pats rather than punches, and the teachers of strong constitution, they had to take months off work suffering from a range of psychological problems – time off on full pay, of course. I even knew one teacher, a teacher of comparative religious studies, who managed to get long-term sick leave due to ‘stress’ during which she secretly taught in another school. I admire people who hold down two jobs but that’s genius and an excuse that possibly exceeds the moral boundaries demarcating ones involving cancer.

In Korea, life isn’t that laid back and most people still make it to work or school through both bad weather and illness and often both! I’ve not had one day off for sickness in four years, not even for a genuine sickness! Even when I’ve had a problem, as I have had today with a buggered knee, I’ve gone to work and simply suffered. This is partly because I’m a personal friend of my boss but it’s also because the kids are decent and working conditions good. I know this isn’t the case in all Korean schools, but it is in mine. But on a day like today, with Daegu buried in snow, the temperature freezing and the visage from my one-room like a scene from The Day After Tomorrow, I feel a yearning, a pang for something British and for once it’s not roast beef, roast potatoes or a pint of British bitter. The adverse weather conditions have initiated a cultural call, a siren invoking me to invent an appropriate excuse and play hooky and doing so is a cultural institution as British as fish and chips. If I was British Rail the announcement on all stations throughout the next few days would be, ‘services suspended until further notice!’ Suddenly, I realise the mild headache I felt all last night, that would otherwise have been the initial stages of a brain tumour, are just my imagination. Reluctantly, I pull on my coat and gloves and head out into the Arctic winter, on my way to work!

Footnote – You know how every two hundred photos you take you have one that’s actually decent? Well. yesterday I had two which encapsulated the conditions which inspired the content of this post. And then, after ‘processing’ them they were somehow deleted. I was quite pissed off! Hence the Winter 2007 photos.

© 林東哲 2011 Creative Commons Licence.

Basic Kimchi Recipe (adapted for those living in the UK)

I have a number of friends and family in the UK, most notably my sister, who have been asking me to give them a kimchi recipe despite there now being many great recipes available on the Internet. So, I have written up a recipe I use when in the UK where I can’t always get authentic ingredients and I need to make substitutions.

There are many different cabbage kimchi recipes encompassing different styles to regional variations. The fact kimchi is so varied makes it exciting and without doubt, everyone who makes kimchi does so slightly different from someone else. For Koreans, when mum makes kimchi, and I’ve only met a few men who can make it, their hands invest it with love. This is the recipe I use for what is basically a straight forward kimchi comprising the basic ingredients.

Kimchi is very easy to make but it helps if you have some knowledge of how decent kimchi tastes so you are able to assess your endeavours and make adjustments to improve future attempts.

There are 9 basic ingredients:

Cabbage – Chinese leaf (called napa in the US). In the UK places like Tesco sell these but they are white, small and very stemmy. You will need 4 of these.

Mooli – once again this sometimes appear in supermarkets though they are small, skinny and bendy. Turnips, 3 0r 4 make a suitable alternative.

A whole bulb of garlic.

An inch or so of ginger. (I often omit this)

A bunch of chives or spring onions. (the type of onion Koreans use I have not seen in the UK)

Rice flour, though I have used plain flour. Not all recipes use this but I prefer paste slightly clingy)

Fish sauce – in the UK Thai Nam Pla is fine including ‘Squid’ brand.

Salt, like a whole box or packet. You will need Kosher salt or sea salt and not table salt.

Korean red pepper powder. You cannot substitute this but I have ordered it with easy in British Oriental supermarkets.

A good size plastic tub – like a Tupperware tub.

(Sugar – not all recipes use this)

Stage 1 cabbage preparation

Without any doubt the most neglected part of recipes on kimchi involve salting, and hence wilting the cabbages. All my early failures at kimchi making resulted from recipes that failed to explain this process. Getting this right is crucial but it is very simple.

1. Immerse cabbages in water. Then trim off discoloured bases, remove any bad leaves, and using a good knife begin to cut the cabbage in half from the base. Once about a third of the way into the cabbage, remove the knife and then simply tear the cabbages in half. If you have large cabbages you would in fact quarter them in this manner but if they are the small ones I’d simply half them.

Let the cabbages drain but don’t dry them.

Double check your using sea salt! Lay the cabbage half on its back, and then begin sprinkling salt on the lowest leaf, on the inside. You’ll need to raise the rest of the cabbage up to access it and at times, with a small cabbage, you can hold it in the palm of your hand and finger the leaves apart. Make sure you sprinkle salt into the base area where stems are thickest. You don’t need lots of salt, just a good pinch for each leaf. This process is finicky with small cabbages.

When all salted, put the cabbages in a bowl, throw a handful of salt over the top and then add a cup or two of water. Then simply leave them until wilted which may be between 2 hours to over night depending on the temperature. Turning them a few times during salting is useful.

How do you know when the cabbages are ready to paste? First they will have reduced in volume considerably and the container will contain a lot more water. Most importantly, the cabbages should be limp and floppy j. A good test is to wring one and it should wring just like a cloth, without tearing.

Next, rinse them 3 times. To prevent the kimchi being too salty, you can immerse cabbages in water and feel where excess salt is as it will have a slimy feel. Simply remove this with your fingers. Make sure you wash between the leaves.

Finally, wring them to remove excess water which will otherwise dilute your paste. The cabbages are now ready to paste.

Stage 2 Preparing the other ingredients.

Grate the mooli (white turnips) and squeeze any fluid from them

grate the ginger

crush the garlic

chop the spring onions (chives)

Mix 2 tablespoons of rice flour (or plain flour) in a little cold water, until it is a runny paste, then add this to a pan containing 1 and a half cups of water. Heat this until it begin to boil, stirring it constantly and adding any additional water until it resembles porridge. As it begins to boil you can add a 1 tablespoon of sugar but this is optional. The ‘porridge’ provides some body to the paste and many Koreans do not use it. Personally, I quite like a thicker paste on kimchi though not too long after fermentation, the paste will have become diluted regardless.

Stage 3 making the paste

Put the rice flour porridge in a large bowl

Add half a cup of fish sauce

3 cups of red chili powder

Add garlic, ginger, onion and mooli

Mix them all together into a paste being careful not to burn your fingers on the porridge mix.

Stage 4 pasting up the leaves

This process is almost the same as salting the leaves; lay each cabbage on its back and staring with the inside lowest leaf, paste on the mixture. Any leftover paste I simply spread over the top unless there is a lot when I might freeze it for later use. Segments should be placed in a Tupperware container with each segment being laid in a head-tail-head order. They pack better this way.

Some General Points

Where to store kimchi – basically, if it’s summer in the fridge and if winter, somewhere cold but not freezing. Kimchi ferments and as it does so the taste is altered. Part of the fun in making kimchi is in controlling the fermentation so you keep your batch in the condition in which you best enjoy it.

Fermenting kimchi – You can eat kimchi immediately. Prior and during fermentation, kimchi has a very fresh taste where individual ingredients are distinct. The kimchi will also be lively in colour. At this stage the kimchi can be salty but as fermentation and infusing continues, saltiness is lost. Some saltiness or even heat (spiciness) can be compensated with some additional sugar. If it has lost saltiness you can adjust this at this stage. Stems may still be slightly firm and thick stems may still have a little crunch left in them despite being wilted. Be prepared for some bad smells during this period. Fermentation can last up to a week depending on temperature and in comfortable room temperature (21 degrees) you can expect the lid of the Tupperware container to pop open about once every 24 hours. I’ve slept in the same room as fermenting kimchi and no longer find the aroma unpleasant but the released gasses will easily scent a room with what some will consider a very unpleasant smell.

Fermented kimchi – individual flavours are much less distinguishable, saltiness is reduced and the paste has probably thinned and increased considerably. Don’t worry; this is delicious in stews and soups. I often make minor adjustment to saltiness and sweetness.

Aged Kimchi – aged kimchi draws your mouth with its sourness and if you appreciated this type of kimchi, there is a point, which differs for each ‘connoisseur,’ where the balance of saltiness, acidity, and sweetness combine to provide an exquisite taste. I often add a little sugar or salt to this kimchi in order to balance the mixture exactly as I like it however; it never produces the same sensation as it does when the balance is naturally right. Aged kimchi is slightly yellower in colour and the stems slightly translucent. What aged kimchi might lack in lustre is compensated by its mature taste.

Once you know how you like kimchi you can move your Tupperware pot in order to slow down or suspend fermentation. After the kimchi has stopped releasing gas, it will continue to mellow but at a much slower rate and during winter months or when it is kept in a cool place or the fridge, the taste will differ very little over several months.

Very old kimchi, over six months might have mould on the surface but don’t throw it away; wash the mould of the top segments and the kimchi is still edible but much better for use in stews.

If you can obtain minari, as you can in Korea, a bunch of this, chopped can be added along with the spring onion, garlic and ginger.

Good luck and don’t be afraid to experiment as you gain experience!

© 林東哲 2011 Creative Commons Licence.

The Boy on the Stair

For the last two years my alarm call has been the footsteps of a high-school boy. I’ve never seen him and the only reason I assume it’s a boy is the manner in which he descends from the apartments, perhaps two stories above; he seems to take five steps at a time and it only takes him seconds from beginning his descent to exiting the building. The head of my bed is against the wall at the foot of which he lands as he jumps down each flight of stairs. And I assume he is a high school student because no middle school boy would be in such a rush to get to school.

With the winter vacation, his footsteps and my alarm call have been absent but with the start of the ‘prep’ week during which students return to school and settle into their new classes, his feet once again provided a noisy reveille. The ten-day spring break now begins and their will be a short respite before he returns, all the more frantic as I would assume this is his third year (고삼) and the most frantic year of a Korean student’s life.

© 林東哲 2011 Creative Commons Licence.

Monday Market – King Oyster Mushroom – 새송이 버섯

In Britain, we tend to have both mushrooms and toadstools. ‘Toadstools’ is a term, though not exclusive in its use, to describe those cap bearing ‘mushrooms’ which are inedible or poisonous. Unfortunately, many toadstools are indeed edible and there are a number of examples I am competent enough to pick and eat. One of my favourites, which grows and is eaten in Korea, is the parasol mushroom (갓 버섯 – lepioptera procera). In England, this wonderful mushroom is prolific but few people pick it and it is unavailable in shops.

Koreans, like many other European countries, are much more adventurous in their culinary and medicinal use of fungi and a wide range of exotic mushrooms are available. The king oyster mushroom (새송이 버섯 – pleurotus eryngii) is common in markets and supermarkets and is also known in Britain as the king trumpet mushroom or French horn mushroom. In Korea it is a common ingredient in stews and a favourite skewered between meat and onion. Though not particularly flavoursome, when cooked it has a meaty, abalone-like texture. Though difficult to find, as they often grow under forest ‘debris,’ they are easy to cultivate.

Korea is one of the leading producers of the king oyster mushroom and grown in temperature controlled environments with air cleaning, water de-ionizing and automated systems, farming is high-tech. One of the most successful producers is Kim Geum-hee who now owns six high-tech farms producing over 5 tons of mushroom daily.

Kim Geum-hee is an adorable character and one of Korea’s outstanding agriculturalists. I fell in love with her personality after just one video partly because the added translations are a little ‘studenty’ but ironically enhance the videos imbuing them with an enchanting cuteness.

The videos about her success are interesting and well worth watching. ‘Kim Geum-hee ‘had a dream about mushroom,’ and later, ‘after graduating fell in love with mushroom.’ Oh, dear, I have bad thoughts. When I see a room full of cap-type mushrooms I can’t help being reminded of penises. I’m sure many other westerners would have the same response and besides, the stinkhorn’s botanical name is phallus impudicus and before it was biological classified it was known as, ‘fungus virilis penis effige‘ ( Gerard, 1597). It’s not just me! You can poke a Korean in the eye with even the most phallic of fungi, of which there are a number of amazing varieties, and not the slightest link will be made to a penis. To Koreans that offensive fungi is simply a mushroom!

There are some excellent ways to use the king oyster mushroom:

© 林東哲 2011 Creative Commons Licence.

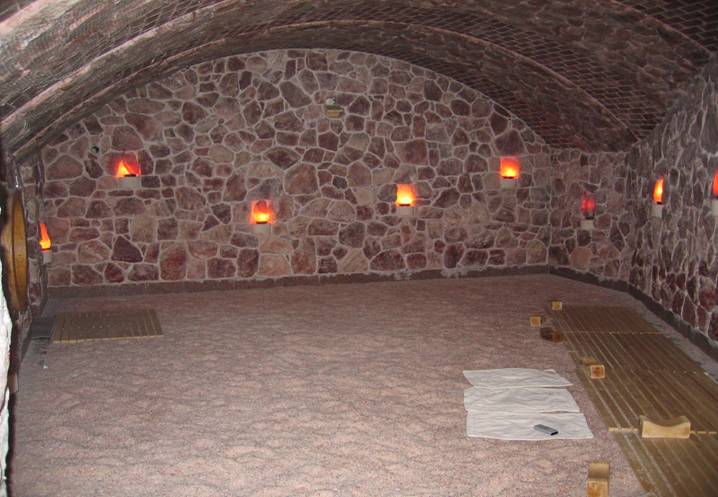

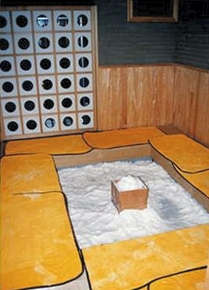

Bathhouse Basics (12) – The Salt Sauna 소금방

Salt saunas can be found in both bathhouse and jjimjilbang and they are one of my favourite destinations. They tend to be a slightly specialist facility which means you won’t find them in every establishment. You will find the salt experience differs between that offered in a bathhouse and that in a jjimjilbang. Jjimjilbang salt saunas often have walls and or ceilings made from rock salt or they have a large area filled with coarse rock salt in which you can submerse your limbs and body and enjoy the radiant warmth. In a bathhouse, a salt sauna usually has large pot of salt which you rub over your body allowing the salt to both scrub and purge you skin clean. The bathhouse salt room is often combined with other properties as it may, for example, have jade or bamboo charcoal walls walls.

The bathhouse salt sauna is one of my favourite places and you really do feel clean after rubbing your body with salt and then allowing it to dissolve as you sweat. I usually take a small bowl of water in with me as this helps to make the salt cling to your body and don’t forget to take a towel or large scrubbing cloth in with you as often the seats are wooden and they can burn your backside.

As a point of interest, salt is very useful at removing smells and in a Korean market you can buy fresh mackerel which has been sprinkled in salt which you then wash off before cooking – it reduces the smell of the fish as it cooks. I’m not sure however, how well this works on body odours!

© 林東哲 2011 Creative Commons Licence.

9 comments