Kimchi Bubble and Squeak – Fusion Kimchi

Bubble and Squeak was a favourite dinner when I was a boy and was one of those meals in which you could use various leftovers. It is an English food that along with most other typically English meals, toad in the hole, faggots, mince and onions, etc, you rarely find in a restaurant.

Here is a recipe for bubble and squeak using kimchi. As always the recipe is a template and I have provided some ideas for variations.

INGREDIENTS

•1 pound of potatoes

•salt and pepper

•1 cup of chopped kimchi

•water

•oil (lard)

•1 onion – chopped

METHOD

1. Boil the potatoes for 25 minutes, drain and mash (butter, milk, cream etc, can be added). Of course using left over potatoes is perfect. Add salt and pepper.

2. Mix the kimchi and mashed potatoes.

3. Fry the onion in a little oil in a heavy frying pan

4. Add the potato and kimchi mix to the pan and press down until it is like a cake – cook for 15 minutes.

5. Remove from the Pan onto a plate keeping the shape as much as possible. Make sure to scrape out the frazzled and burstled bits from the bottom of the frying pan. Re-oil the pan, heat, and put contents back in the pan, this time, upside down. Cook for 15 minutes.

6. Serve with an egg and/or bacon, sausages and or or with tomato, brown or Worcestershire Sauce. How about some cheese sprinkled on top or simply a sprinkling of sesame seeds and a little sesame oil. Just use your imagination.

OBSERVATIONS

My mother and grandmother never patted it down but just cooked it in the pan turning it every five minutes or so and scraping the frazzled bits, folding them into the mixture. It is the frazzled potato and cabbage which are the most enjoyable.

VARIATIONS

Bacon is a great addition at stage 3.

For a full fat version use lard in the frying process and add milk or cream and butter to the potato at stage 1.

©Amongst Other Things – 努江虎 – 노강호 2012 Creative Commons Licence.

Usually Cabbage (but whatever) Bean Paste Soup (배추 된장국)

Key Features: a healthy side dish, breakfast or lunch, adaptable, which is chilli and kimchi free. It also contains no oil.

Ten years ago there was a big fad in the UK for a miracle diet known as ‘The Cabbage Soup Diet.’ I actually lost over 17 pounds in 10 days but as far as diets go it was doomed to failure. The first week, as your body lost water, your weight correspondingly plummeted. However, after a week or so, the rapid reduction leveled out and with it the realization that while the grim regime was bearable if the pounds fell off, it was torture if they didn’t.

The diet revolved around the most disgusting concoction you could possibly make with decent ingredients: cabbage, onion, tinned tomato, green pepper, celery and a stock cube. For the first three days the soup was consumed for every meal and you could enjoy as much of it as you liked. It was so gross I would liquidize it and drink a pint of it in a few gulps. The smell and taste were nauseous and so it was taken like a medicine. By the third evening, you could eat a jacket potato and a knob of butter the size of which wasn’t stipulated – hence it tended to be large. The cabbage soup destroyed any pleasure in eating and guaranteed failure was not only terminal, but when real food could be accessed it would be consumed with a vengeance.

Bean paste soup with Chinese leaf cabbage (Napa) is a Korean classic and probably contains only slightly more calories than the infamous and ghastly diet soup. It is however, infinitely tastier. As you will see in the ‘alternatives’ section, cabbage can be substituted by with other items.

I know many people are put-off Korean food because they think everything is spicy or contains kimchi. This is one of the myths surrounding Korean cuisine, the greatest of which is the myth that Korean regularly eat dog. Here is an example of a Korean soup which uses neither kimchi nor any form of chilli. While it might not qualify for Westerners as dinner, served with rice, side dishes or even alone, it is an excellent breakfast or lunch. It often accompanies other meals as a side dish where it is shared.

There are countless variations on this soup. Using this basic recipe, I often use chopped pork or cubes of tofu. Similarly, you can also add chilli. The shepherd’s purse can also be omitted.

MY DEFINITIVE RECIPE

1 cup = 180ml. T=tablespoon (15ml), d=dessert spoon (10ml) t=teaspoon (5ml)

This recipe is ideal for one, or as a side dish – double ingredients for each additional person

SHOPPING LIST

1 cube (4 cloves) of crushed garlic.

Half a medium onion or leek

0.5t of dashida (다시다) or a stock cube

1,5 T of bean paste (됀장)

1 cup of Chinese cabbage leaves, previously blanched outer leaves are good.

Shepherd’s purse (냉이) about a third of a cup.

3-4 cups of water

1T flour or rice flour (optional)

See also suggested accompaniments at the bottom of the page.

EQUIPMENT

Ideally as an earthenware pot or ‘ttukbeki’ (뚝배기) or a heavy bottomed sauce pan.

RECIPE

In a heavy bottomed pot or Korean earthenware ‘ttukbeki,’ place:

1. 3 cups of water and all other ingredients. (7 ingredients)

2. Bring to a hard boil for 5 minutes and then reduce to a simmer for a further twenty minutes.

3. Optional – mix the flour in a little cold water and add to the soup. Stir for two minutes and serve.

SERVING SUGGESTIONS: Serve with an accompanying bowl of rice and side dishes. It can also be served as a side dish with other dishes.

ONGOING NOTES:Try using a small amount of pork, or diced tofu. You can also substitute cabbage spinach, crown daisy, chrysanthemum (쑥갓 ), burdock leaf (우엉) or mugwort (쑥).

© 努江虎 – 노강호 2012 Creative Commons Licence.

Kimchi Omelette – Fusion Kimchi

Key Features: easy and quick to cook, adaptable, Korean fusion, snack or fusion side dish

I’m constantly on a diet and freeze anything I might be tempted to eat when feeling peckish. So, one evening, feeling a little hungry I looked in the fridge to see what items might possibly make a quick snack. Five different pots of kimchi and a couple of eggs were all that confronted me.

So, I whisked two eggs and then added some chopped kimchi. The result was quite delicious.

MY RECIPE

1 cup = 180ml. T=tablespoon (15ml), d=dessert spoon (10ml) t=teaspoon (5ml)

This recipe is ideal for one – double ingredients for each additional person

SHOPPING LIST

2 eggs beaten in a bowl

Half a cup of finely chopped kimchi

1t of sesame oil.

1t of sesame seeds

a little ordinary oil – just enough to stop the egg sticking to the pan

See variations and suggestions at the end of the recipe.

EQUIPMENT

Frying pan and bowl

RECIPE

1. Fry the chopped kimchi for a few minutes in a little ordinary oil.

2. Fold kimchi into the beaten egg

3. Put the mixture back in the frying pan

4. Drizzle a little sesame oil and a sprinkle of sesame seeds just before turning the omelette.

Serve with a little tomato sauce or whatever takes your fancy.

©Amongst Other Things – 努江虎 – 노강호 2012 Creative Commons Licence.

Bratwürst and Kimchi – Fusion Kimchi

My local E-Mart has started selling quite decent German bratwürst and I recently tried them with kimchi. Well, bratwürst and sauerkraut is a common combination so I was thinking a spiced up version should be quite tasty. They worked well together and were okay with mustard but personally, they worked better along with a little potato salad. My kimchi is on the spicy side and the mayonnaise in the salad offsets this.

©Amongst Other Things – 努江虎 – 노강호 2012 Creative Commons Licence.

At Least it’s not a Cockroach – Rice Weevils (쌀벌레)

Over the long humid summer, one problem with rice is infestation by rice weevils. Their presence is noticed by small black additions to otherwise white rice. There are several means of keeping them out of your rice container, one of them being to place dried chillies and a head of garlic in the same container. Others are the use of airtight containers or placing your new bag of rice in the freezer for 24 hours. This method isn’t the best if you buy rice by the sack.

The best deterrent is a packet of ‘Rice Weevil’ (쌀벌레, by 방충선언), which costs about 4000 Won and is widely available. You simply snip open the packet and it sticks on the inside of your container. The smell is pungent and very similar to intense wasabi (horseradish) but it stays in the container and doesn’t flavour the rice. One packet gives 3 months protection.

© 林東哲 2011 Creative Commons Licence.

Seduced by a Guatamalan Beauty

Finding a decent coffee in Korea is not difficult, but finding one where coffee’s sophistication isn’t assaulted by tasteless music, is. Most of the large coffee franchises and restaurants pump out shite music which has a broad appeal but I don’t particularly want to drink a coffee or eat lunch to the same music I’ve also been forced to listen to in the gym or by those teenagers zig-zagging down the road on their noisy hairdryer-powered mopeds. I suppose it could be worse; it could be muzak!

I used to love a good cup of English tea, preferably Earl Grey though Lady Grey is also a favourite. Tea is one of the most refreshing beverages but I’ve learnt that there is something amiss with tea in Korea as there is something amiss with soju in the UK or Pimm’s No. 1 consumed indoors, in winter. My local Home Plus was selling boxes of Twinning’s Earl Grey last year at the amazing price of 2500 Won (£1.25) for 50 bags. However, whether it was the water or the milk, I could never brew a cup that was decent, let alone one the experience of which was sublime. And now I’ve become a coffee head!

If you follow the correct procedure you can guarantee a decent coffee with every brew but the perfect cup of tea is elusive and the method not as quick to reveal the full potential as is coffee. No matter how many cups of coffee I make, or which procedure I follow, every cup is simply okay and certainly coffee’s reliability to produce a good brew is its failing because in the randomness and unpredictability of tea, lies its greatest strength. And no matter how many different types of coffee I sample, they all seem to taste the same which I suppose is a reflection of my ignorance. Teas however, are much more distinct and their flavours and subtleties don’t require learning to be appreciated – and least not if your British.

The perfect ‘cuppa’, worthy of a lengthy, ‘shi-won-hada’ (시원하다) which in this sense approximates, ‘oh, heavenly,’ is dependent upon something beyond the brewing method and even the closest adherence to brewing principles fails to guarantee its attainment. With tea, you accept that while most cups will be good, perfection is elusive. Yesterday, I decided to have an Earl Grey in Mr Big; it was a disappointment, the tea was served in a glass mug and I had to ask for milk. Earl Grey with milk never looks appealing in a glass cup as it is so pale and insipid and though it had a perfumed bouquet, as you would expect, and seemed to contain fresh tea leaves, though they could just as easily have come from a tea bag, there was something missing. So, until I’m back on British shores I guess I’ll have to be content with coffee.

My favourite coffee shop is the ‘Coffee and Bun’ near Migwang and almost directly next to the new football stadium sized coffee shop, (Korea’s most popular), ‘Coffee Bene.’ ‘Coffee and Bun’ is run by a young man who is totally obsessed with coffee and who has almost taken me under his wing as an acolyte. I can no longer venture here without being shown the latest coffee brewing paraphernalia or being asked to compare some beans. I don’t particularly mind, the café has an intimate atmosphere and usually the music is gentle and in the background and certainly has more sophistication than the pop-pap which is universally pumped out. If you thought coffee tasting was simple, let me assure you it is every bit as complex as wine tasting and among connoisseurs is known as ‘coffee cupping.’

Unlike tea tasting, which is a fairly cheap hobby, coffee cupping can be expensive. Over several sessions Chong-min has paraded his entire range of coffee brewing utensils. Two pots in which boiled water is allowed to cool before pouring, one stainless steel, the other copper, cost 140.000 Won (£70) and 180.000 Won (£90), respectively. As the water needs to be poured at 195-205 degrees Celsius, a suitable thermometer is needed. Next, he has a collection of 5 coffee drippers in differing designs one of which is made with a fabric, while another, at 50.000 Won (£25) is copper. You would think coffee drippers a fairly standard item but in several of the books from the growing coffee library in a corner of his café, I can research their various designs and their pros and cons. Even the cheapest dripper (5000 Won) is cataloged in his books. Another glass utensil combines a coffee pot and dripper and the paper filters, almost the size of A4 paper which Chong-min folds with the dexterity of an origami master, are bought from the USA and cost around 200 Won each. In my ignorance, I’ve always used a food processor or blender to grind my coffee and now I learn this is vastly inferior to the conical burr grinder which guarantees consistency of grain. ‘Blade grinders’ simply smash the beans about producing an inconsistent ground of both powder and more sandy grains.

When the water reaches the magical temperature of around 92 degrees Fahrenheit, I am required to drip the water over the grounds in a spiraling motion after which we wait for several minutes. Naturally, we have scrutinised the beans, feeling them, smelling their aroma, assessing their oiliness, observing their colour and the grounds we have sniffed and sifted between fingers. We eagerly wait to sample the brew but as usual, the taste is not much different to the coffee I produce in my cheap coffee press using fairly regular beans smashed up in a blender.

I was beginning to perceive a good cup of coffee, more like an okay cup of coffee and in much the same light as I perceive a glass of Coca Cola, ie, as simply a fizzy drink with no greater potential to satisfy than any other fizzy drink, but the mediocrity of which is inflated beyond the realms of reason. I was beginning to think I’d been hoodwinked into searching for something that did not exist and learning a language, a jargon, that made something out of nothing. That was, until Chong-min presented me a cup of Guatemala (COE – cup of excellence). It wasn’t even brewed by means of his epicurean paraphernalia all of which I was beginning to suspect were the implements of an international coffee conspiracy. Even if I had not been aware of the superiority of this particular coffee, it would have made an impression. It’s announcement lay somewhere between an oral orgasm and a sledge hammer. I have no idea what was fantastic about it any more than I can really tell you what constitutes that elusive cup of sublime tea. To have deconstructed its superiority with descriptors like, ‘rancid/rotten’ and ‘rubber-like’ would have destroyed the moment. Like tea, once perfection is presented, it’s potential lasts only a few minutes. The ‘moment’ becomes even more appreciated when Chong-min tells me the beans cost 40.000 Won (£20) for 100 grammes. That’s a staggering 8 times the price of the most expensive supermarket coffee where 100 grammes costs around 5000 Won (£2.50). To the ignorant at least, and in the eyes of coffee cupping connoisseurs, I’m ignorant, no descriptor bolsters the taste of coffee more than ‘cost’ and I’m glad I was hit by the oral orgasm before I learned its price because price often has the capacity to turn shit into gold. Monk fish, in Korea for example, is prolific and cheap but in Britain, where at one time it was a poor man’s substitute for scampi, a massive hitch in price has reinvented it as an exotic, expensive delicacy patronized by the numerous celebrity chefs who entertain the nation while they sit down to TV dinners and food largely the product of factory systems. Monk fish is now the gentry of the sea, infinitively superior to that former bulwark, the salmon and vastly more sophisticated than the old scampi it used to mimic. Nothing inflates taste more, or subjects it to more scrutiny, or provides for it a jargon which only erudition can elicit, than cost.

I am pleased I appreciated the Guatemala (COE) before being made aware of its price and had considered giving up the pursuit of the perfect cup of coffee, which in effect really entails the acceptance of my ignorance. Now I can dispense with trying to learn perfection and in this case treat myself to the experience when I feel the need. Sadly, at 40.000 for a 100 grammes, my average weekly consumption, I’ll drastically have to reduce the number of cups I drink.

Find Coffee and Bun on Wikimapia

© 林東哲 2011 Creative Commons Licence.

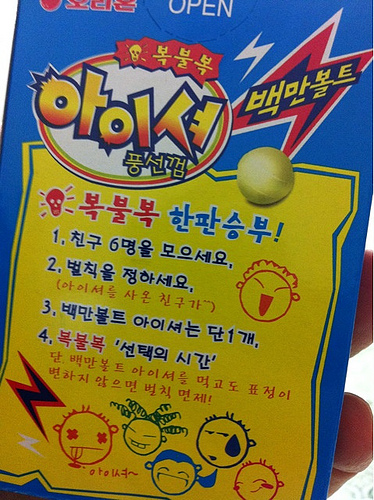

Punishing Naughty Students with Ai-Sh-Yo! (아이셔)

Specially for Children’s Day! In every box of Ai-sh-yo, is an intensely sour gum. You can’t distinguish the gross one from the others in the box. If you want to punish your students or get some pleasure after they’ve pestered you all week for Children’s Day candy, you can do so in this random manner.

Yea, I know my Korean is shitty! And here are some photos capturing the moment.

Further References

© 林東哲 2011 Creative Commons Licence.

More on Cabbage Kimchi – Some Guidelines

This post was originally published in February 2011 and is now updated.

I am now quite proud of my cabbage kimchi, a skill which has taken me about ten years to get right. One reason why it takes a long time to make decent kimchi is that you have to develop a sense of what constitutes a good kimchi and an awareness of kimchi at different stages of fermentation. Unless you have a cultivated appreciation of what Kimchi is, and by that I mean an awareness of kimchi that a Korean would enjoy and not what you personally think it should taste like, your kimchi will never be authentic. The subtleties of kimchi are as intricate and extensive as wine or Indian curry and an appreciation is important if you are to use a recipe to guide you.

There exist many recipes for cabbage kimchi, regional, personal and for accompanying certain meals; bo-ssam (boiled, sliced pork, 보쌈) for example, uses a special type of kimchi. I am concerned here with the standard type of kimchi that accompanies the majority of Korean foods and which can be divided into two categories, fresh and sour. There is of course, a range of flavours in between these extremes. Many Koreans have a preference for one or the other and foods which use kimchi as a major constituent, as for example with kimchi stew (김치 찌개 or 김치찜), suit one or the other.

I’m told by Korean friends that big cabbages are not the best to use and that medium sized ones, which compared to Britain are enormous, are the most suitable. The outer leaves are trimmed and unless damaged these shouldn’t be thrown away as they can be used in other recipes.

One of the most persistent problems I faced was the most crucial; namely getting the salting process right. Even cook books sometimes overlook what is a seemingly simple procedure. When the prepared cabbages are ready to paste with your kimchi paste mix, they should resemble a dishcloth by which I mean they should be floppy and it should be possible to wring them without them tearing. If you get your kimchi paste wrong you can always adjust it. Even if you subsequently discover your kimchi is too salty it will mellow as it ferments but should the kimchi fail to wilt properly it will not be easily rescued.

Many recipes gloss over the salting process and only this week I read Jennifer Barclay’s book, Meeting Mr Kim (Summersdale, 1988). The book is an interesting account of life in Korea and not a cookbook, but her kimchi recipe, and she is not alone, simply directed you to soak the cabbages in salted water. If as recipe does not explain the salting process in some detail, tread with caution! I once used an entire big bag of table salt in which I soaked the cabbages for several days and they still failed to wilt effectively. The salting process is actually simple if you use a coarse type of salt (such as sea salt or if in Korea 굵은 소금)) and sprinkled between the leaves is all that is required to wilt the leaves in several hours, depending on room temperature. When I make kimchi in the UK, I am forced to use cabbages which are almost white in colour, very stemmy, and which are too small to quarter but even these wilt if treated properly. After salting the washed and wet cabbages they can be placed in a bowl or sink, sprinkled with extra salt and a few cups of extra water and left. Immersing them in water isn’t necessary. In hot weather the wilting process is much quicker. You should notice the cabbages almost half in volume and soon become limp, floppy and wringable.

Like rice, traditionally, Koreans rinse the cabbage three times. I have learnt it is much better to rinse them thoroughly, perhaps removing too much salt but this can always be remedied later. However, if you use the correct ammount of salt and don’t sprinkle excess on, three rinses are adequate. You can feel where salt residue remains as the stems are slimy and you can remove these by simply rubbing your fingers over them.

Salty kimchi will mellow with fermentation, it is probably better for it to be not salty enough than too salty, especially given the concerns over salt and blood pressure. One hint Mangchi suggests is adding some thin slices of mooli (무) if it is overly salty.

A good kimchi paste will cling to the leaves like a sauce so it is prudent to drain the segments and even wring water out and this will prevent your kimchi becoming watery as the cabbages ferment.

Plenty of recipes, online and in books, will guide you through making the paste but my all time favourite is Maangchi. Her website is enormous and her videos on Korean cooking are well presented. Here you will also find other ways to use kimchi as well as many other types of kimchi, cabbage and otherwise.

British friends who have since become lovers of kimchi often ask me how long it will keep. I tend to keep kimchi in the refrigerator in hot weather and somewhere cold, but not freezing, in winter. If you like kimchi fresh (newly made,) keeping it cool or cold will delay fermentation. If you like it sour then you can use a warm place to speed up the process. I tend to juggle things in order to better control fermentation. I made my last batch of kimchi in November and the tub in which it is stored has stood on my balcony almost 6 months. I have now moved it to the bottom of my fridge to mellow indefinitely. I have used kimchi that was over 6 months old and which had white mold on the top but this washed off and the underlying cabbage was excellent as the basis for a stew.

© 林東哲 2011 Creative Commons Licence.

Monday Market – Spicy Crab (양념게장)

Yang-nyeom gejang (양념게장), is basically raw crab marinated in a chilli condiment. There are many regional variations of this side dish (반찬) and though the most common crab used is the horseshoe crab (꽃게), others, including freshwater crabs, are utilized. Yang-nyeom (양념) is a spicy sauce which is very common on fried chicken. Another version, kan-jang gejang (간장게장), marinates the crabs in soy sauce.

The sauce is sweet and spicy and the soft flesh of the crab is sucked out of the cut portions. I didn’t really like this the first few times I encountered it but it has an appeal and like many Korean foods, gradually grows on you.

© 林東哲 2011 Creative Commons Licence.

A Candy for the Teacher

What’s that noise you make in your language when you’ve eaten something intensely sour, like lemon or a kumquat which isn’t sweet enough to rescue your distaste? In English-English it might be ‘shhh-it!’ In Korean it’s ‘ai-sh-yo’ (아이셔), though in practice it probably sounds more like ‘ ai-shhhhh-yo!’ The duration of the ‘sh’ a measure of intensity. Not sure what I mean? Let me elucidate; this is ‘sh-it!’ or ‘ai-sh-yo!’:

Apart from being the sound to accompany something unpleasantly sour, like munching on a lemon, Ai-sh-yo is also the name of a chewy confectionary. Kids love to give these candies to teachers and they can be considered the Korean equivalent, innocent and friendly, of spitting in your coffee or putting a tack on your seat. When I was first offered them I noticed a strange expectation on students’ faces, a twinkle in their eyes and the slight anticipatory twitch of a smile but took little notice; I’m orally fixated and the candy was quite nice, initially a little tart and tangy but quickly rescued by sweetness as you continue to chew. I’d eaten quite a few over the week until I discovered their more sinister purpose

I was busy chewing, waiting for the sweetness to curb the rapidly soaring sensation of intensified sourness… Then I realised, with a curse, ai-shhhh (the Korean equivalent of ‘fuck!’), that there wasn’t an iota of sweetness in it but a solely nasty sourness. My students were in hysterics by the time I spat it into a tissue.

Yes, in every blue packet of the gum, 450 Won (about 25 pence) exists one surprise candy that is simply revoltingly sour. The yellow packet is a tart candy that starts off sour but mellows.

‘Ai-shhhhhhhh-yo!’ ‘Super sour flavour in it.’

Further references

Punishing Naughty Students with an Aishyo

© 林東哲 2011 Creative Commons Licence.

1 comment