Monday Market – Mackerel Pike (꽁치)

One of my favourite barbecued or grilled fish which often appears as a side dish, the mackerel pike, often called saury, is a long, thin fish with a distinct ‘snout.’ It is an oily fish and is usually grilled whole without being gutted. When eating it however, avoid the gut as it is horribly bitter. Rather like mackerel in taste and texture.

© 林東哲 2011 Creative Commons Licence.

It’s Kimchi Time – April 26th 2011

This batch of kimchi turned out to be a further improvement on my technique. My cabbages were large and I have since been told that the best cabbages are not the largest, but ideally more middle sized ones.

- Preparation – Unless the outer leaves are very damaged or spoiled, keep them as they are excellent for use in bean paste soup and numerous other recipes.

Pasting – I usually add ginger but decide to omit it from this batch. Further, I reduced the amount of down to 2 cups but I feel this is still too hot. When I later made bo-ssam kimchi, I decided that one cup for two fairly large cabbages was still a little to hot and intend reducing it a little more.

For the most up to date and effective recipe for Kimchi, check My Recipes.

©Amongst Other Things – 努江虎 – 노강호 2012 Creative Commons Licence.

Monday Market – Crunchy Crab (방게조림)

Whenever I eat this, which is almost everyday, I am reminded of the kind of oral sensation you might experience if you ate a handful of cockroaches. However, despite the fact a portion of bang-gae cho-rim (방게조림) consists of numerous disengaged legs, claws and bodies in a thick spicy coating, they are quite delicious. Cho-rim is a type of side dish which is prepared by boiling ingredients in soy sauce. While the bodies are somewhat soft, the legs and claws are crunchy and because they are spikey and sometimes sharp, need to be eaten with a little care.

© 林東哲 2011 Creative Commons Licence

Castrated Cake and Bollockless Beer

Recently, a blogger whose posts I regularly read (The Supplanter), has been condemning Korean cake and ridiculing its ersatz quality (Happy Spam Day). The Supplanter has made similar accusations against Korean beer (cASS and sHITE) but he is not a member of the substantial army of westerners that live here, some of them for decades, who continually berate Korean society. And I have to agree with him; Korean beer is shite and their cake, as scrumptious as it looks, is not much better.

I’m not much of a beer drink and if anything prefer what we Brits refer to as ‘real ale’ and I was also spoilt by ten years living in Germany where there is a vast range of decent pils-type lager. Korean lager never quite satisfies and drinking it tends to make me yearn for the real thing. Not only is it weak, watery and blatantly bland, but in every sip is the constant reminder of a chemical process and a factory production line.

Korean cake, at least in appearance, is certainly comparable with the fabulous creations of German torte and such delights as Schwarzwälder Kirchetorte, Sachertorte and kaβekuchen. In terms of taste however, you can expect a tragic disappointment.

Several weeks ago, I had a coffee in one of the numerous Sleepless in Seattle cafés to be found around Song-So, in Daegu. Having learnt not to coax disappointment, I rarely buy anything other than a coffee bun but when I noticed Camembert cheesecake on the menu, I couldn’t resist. Quite a strange concoction, Camembert, chocolate and cream, I thought, especially if you’ve experienced the almost putrefied, overripe Camembert which exudes the slightly pungent pong of ammonia. And Camembert in Korea is also strange as decent cheese is one of the hardest products to buy. I had heard that certain cheeses could not be imported because there were restrictions on foods with certain bacteriological properties. Then there is the theory that Koreans, like the Chinese, haven’t developed a taste for cheese or many other milk products as the climate and pastures for rearing cattle don’t exist as they do, for example, in Europe. Korean cheeses are usually always mild, stretchy and in terms of cheese, totally synthetic.

Well, the Camembert was quite delicious and there certainly was a tinge of Camembert flavour; present but not pronounced and as distant almost as Europe itself. The combination worked but the cheesecake was really just mildly cheesy syntho-cream. And then, last week, when I had some spare cash in my pocket, I noticed a complete Camembert cheesecake sitting in a Paris Baguette bakery. It was certainly very vocal and for a good ten minutes I stood outside the shop deliberating whether or not to buy it and apart from the calories with which I knew it would be loaded, I don’t usually spend 16.000 Won (£8) on a cake. Well, it was Friday and my boss had given me a bonus, so I bought it!

However, my reasoning wasn’t purely gluttonous as I’d hoped to salvage the reputation of Korean cake after reading the Supplanter’s condemnation. I was going to pen a response basically agreeing with his observations but forwarding the Camembert cheesecake as an exception and as soon as I got home took a few photos to help secure my intended argument.

Korean bakeries are certainly adept at creating visual feasts and cakes covered in cream, chocolate and fruit, in a fascinating and artistically inspired range of designs, mesmerize and tempt the viewer. Unfortunately, visual creativity far outweighs culinary inspiration and innovation. My beautiful cheesecake, which looked like an entire mould encrusted round of Camembert, was nothing other than a boring sponge with a lick of creamy substance providing the filling and a thin painting of Camembert forming the facade, and a facade was exactly what it was! As far as sponge cake went it was delicious but cheesecake – it was not!

I have now come to the conclusion there is more value and taste in a humble coffee bun than the entire gamut of glamorous gateaux where a thin wall of creamless-cream, coffeeless-coffee and chocolateless-chocolate hide a either a basic sponge cake or simply more aerated syntho-cream.

© 林東哲 2011 Creative Commons Licence.

Skewered King Oyster Mushroom (새송이 산적)

Skewered mushrooms king oyster mushrooms (세송이) are delicious and easy to make. It’s a versatile side dish which can be adapted to suit vegetarians and lends itself to experimentation.

You will need:

1. Around 4 king oyster mushrooms

2. Half a pound of beef or pork (but I guess it could be prawns or chicken)

3. 4 table spoons of soy sauce

4. 2 tablespoons of sugar

5. a couple of chopped spring onions

6. chopped garlic

7. sesame salt (or salt and some toasted sesame seeds)

8. black pepper

9. Skewers

METHOD

1. Boil the mushrooms for a minute and then slice lengthwise about an eight of an inch thick.

2. Slice the meat the same way

3. Make a marinade of all the remaining ingredients and let mushrooms and meat stand in this for 2 hours.

4. Skewer meat and mushrooms alternately and broil them.

© 林東哲 2011 Creative Commons Licence.

Monday Market – Shepherd's Purse (냉이)

I now realise I have an intimate relationship with this weed developed through years of mowing lawns. Shepherd’s Purse, which has tiny white flowers, is considered a lawn pest in the UK and numerous British gardening websites devote space to facilitating its annihilation.

Such a shame! All I needed to do to clear my lawn of this ‘pest’ was to pull it up and consume it. I have never tired it in British cooking but I’m sure with creativity it could have uses. In Britain, there is a long history of Shepherd’s Purse as an herbal remedy and in China it is used in both soup and as a wonton filling.

I wrote a brief post on Shepherd’s Purse (냉이) last year and made it clear I wasn’t sure how much I liked it. However, I actually bought several bundles and froze them and there was ample to last the entire year. Like many seasonal oddities, especially ones used by grandmothers, as is naeng-i, it’s a case of ‘here today – gone tomorrow.’ Only a few weeks after noticing it, it will have disappeared until next year. Naeng-i really livens-up a bowl of bean curd soup (됀장찌게) and I was quite excited to buy it fresh yesterday. I can’t be bothered trimming off the roots and have one of those mesh balls in which I put whole plants and simply immerse the ball in the soup. Quite a few of my students love naeng-i and apart from telling you how their grandmothers use it, are often excited recounting its flavour.

© 林東哲 2011 Creative Commons Licence.

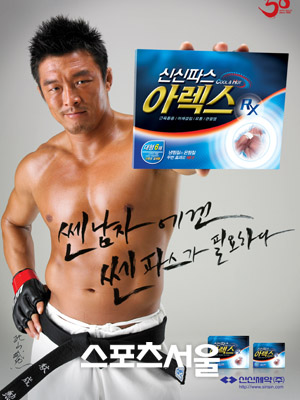

Sucking a Crystal Failed to Realign my Wonky Teeth (Kombucha and Pas 파스)

You can probably buy them back home, I’ve never looked, and you can certainly buy something similar in spray form. Medicines work better when you haven’t a clue what they do. The addition of a language you can’t read plus the fact the ‘medicine’ is traditional, and we all know the allure of oriental traditions in western culture, lends a mystique to the product in which we tend to put more faith than in western medicine, and in which some put excessive faith. Of course, there may be some truth in the power of positive thinking which can boost our health and possibly rid our bodies of cancers and impurities so, I don’t want to be too dismissive of products which help to wish yourself well.

So, for the last month I’ve been laid up with painful knees caused by too many trips down the local mountainside. My injuries stem from October, shortly after an eye infection (red-eye) stopped me using the gym and bathhouse. Instead, I took to the mountains and overdid it and because I go down uneven ground, left-leg leading, I’ve had persistent problems with that knee. The bout of red-eye I contracted began on the very evening of the autumn festival (ch’u-sok), so it was only to be expected that the problems with my knees would flare up on the very eve of the Lunar New Year.

Then I was recommended these large patches (파스) that you basically stick wherever you have a pain. You can buy them in any chemist where they are available in different sizes. And though I can’t read what the patches are supposed to do, I am confident that the miraculous powers of crystal crap are at work. Not only do some of the patches chill the area under them, numbing any pain, but they smell like they might work. There are many different brands and while some are impregnated with conventional analgesics, others seem to be based on oriental formulas or possibly an east meets west medicinal fusion a little similar to pizza and jam or don gasse and tinned fruit. On my second night of wearing them, I went to bed looking like something from Curse of the Mummy’s Tomb, and on every area of my body where I had an ache or soreness, and I discovered a few, I stuck a plaster. I was sure they were working, that was until my doctor (of western medicine) told me all theywould do is reduce pain and totally lacked any further potential.

Where the cold light of science doesn’t shine to dismiss the incredible, we find sanctuary and it’s amazing the things we will subject ourselves to once we’ve taken solace in the concept – which is really no different from religion. A few years ago I spent 18 months brewing a living jelly mold in a warm, dark corner of my house. Every few days I would tap off the liquid on which it floated. Kombucha is a drink believed to have numerous health benefits if drunk on a regular basis but it is difficult to prompt a thirst for it when it’s basically moldy water. However, in fairness, it was palatable and a cross between a mild vinegar and apple juice. It is also mildly alcoholic (0.5%). I have since tried commercial kombucha and it was very refreshing, if not expensive. Kombucha tea is easy to grow and you can birth yourself a batch with a cup of cold, sweetened tea and within a month or so, you too can have a ‘mother’ sized jelly pancake from which you can make other batches at an accelerated rate. I have also heard of people eating the mold, also known as a SCOBY (Symbiotic Colony of Bacteria and Yeast), by frying it. I found it too gelatinous and phlegmy to enjoy. Interestingly, kombucha has a long history throughout various parts of the world, including Russia, Japan and Korea. Indeed, according to Wikipedia, the name ‘kombu’ may have derived from Korea and mold in Korean is kom-bang-i (곰팡이).

My faith in both the kombucha and passe patches (파스) of the non-analgesic variety is borne out of my faith in the mystical powers of eastern medicine and it is the same faith which spurs crystal crap in general as well as the wider interest in Feng Shui (known in Korea as 풍수). The one problem with alternative medicine is that credible practices are lumped together with totally loony ones. I am skeptical, but selectively so and for example; with muscle aches, strains and sprains, or joint problems, I go to an oriental doctor before a western one. Crystal crap however, just seems to lack credibility. I have had several friends give me small crystals with instructions on where to place them and then been told they would ‘heal me’ or help promote ‘good health.’ What I find rather amusing is that in the west such crystals are always pretty and do make lovely ornaments, if that’s your thing, but no one ever suggests you to put a lump of charcoal by your bed, and charcoal is used in Korean bathhouses, and no one ever tells you to use something ugly like coal or a chink of flint. And neither would I mind being recommended some crystal therapy with an ounce of jade except for the fact I’ve bathed and saunaed in, and slept on a couple of tons of it. Every time I go to the bathhouse I end up bathing in one pool or another, or one sauna room where the walls are made from something, jade being the most common, which is supposed to benefit the body, yet I seem no more benefited by such elusive powers than someone who has never set foot in a bathhouse. Perhaps I lack the faith to will myself well when it comes to crystals but, until sucking a crystal can rectify a badly rotted set of teeth, I will retain my scepticism.

Yes, the patches reduced pain and the the kombucha was fun to make and tasted okay!

Chinese names for kombucha include:

红茶菌 – red fungus tea

红茶菇 – red mold tea

茶霉菌 – tea mold.

In Japanese it is known as ‘red tea mushroom‘ – 紅茶キノコ

Interested in kombucha – click this link.

© 林東哲 2011 Creative Commons Licence.

More Tips on Cabbage Kimchi

I am now quite proud of my cabbage kimchi, a skill which has taken me about ten years to get right. One reason why it takes a long time to make decent kimchi is that you have to develop a sense of what constitutes a good kimchi and an awareness of kimchi at different stages of fermentation. Unless you have a cultivated appreciation of what Kimchi is, and by that I mean an awareness of kimchi that a Korean would enjoy and not what you personally think it should taste like, your kimchi will never be authentic. The subtleties of kimchi are as intricate and extensive as wine or Indian curry and an appreciation is important if you are to use a recipe to guide you.

There exist many recipes for cabbage kimchi, regional, personal and for accompanying certain meals; bo-ssam (boiled, sliced pork, 보쌈) for example, uses a special type of kimchi. I am concerned here with the standard type of kimchi that accompanies the majority of Korean foods and which can be divided into two categories, fresh and sour. There is of course, a range of flavours in between these extremes. Many Koreans have a preference for one or the other and foods which use kimchi as a major constituent, as for example with kimchi stew (김치 찌개 or 김치찜), suit one or the other.

I’m told by Korean friends that big cabbages are not the best to use and that medium sized ones, which compared to Britain are enormous, are the most suitable. The outer leaves are trimmed and unless damaged these shouldn’t be thrown away as they can be used in other recipes.

One of the most persistent problems I faced was the most crucial; namely getting the salting process right. Even cook books sometimes overlook what is a seemingly simple procedure. When the prepared cabbages are ready to paste with your kimchi paste mix, they should resemble a dishcloth by which I mean they should be floppy and it should be possible to wring them without them tearing. If you get your kimchi paste wrong you can always adjust it. Even if you subsequently discover your kimchi is too salty it will mellow as it ferments but should the kimchi fail to wilt properly it will not be easily rescued.

Many recipes gloss over the salting process and only this week I read Jennifer Barclay’s book, Meeting Mr Kim (Summersdale, 1988). The book is an interesting account of life in Korea and not a cookbook, but her kimchi recipe, and she is not alone, simply directed you to soak the cabbages in salted water. If as recipe does not explain the salting process in some detail, tread with caution! I once used an entire big bag of table salt in which I soaked the cabbages for several days and they still failed to wilt effectively. The salting process is actually simple if you use a coarse type of salt (such as sea salt or if in Korea 굵은 소금)) and sprinkled between the leaves is all that is required to wilt the leaves in several hours, depending on room temperature. When I make kimchi in the UK, I am forced to use cabbages which are almost white in colour, very stemmy, and which are too small to quarter but even these wilt if treated properly. After salting the washed and wet cabbages they can be placed in a bowl or sink, sprinkled with extra salt and a few cups of extra water and left. Immersing them in water isn’t necessary. In hot weather the wilting process is much quicker. You should notice the cabbages almost half in volume and soon become limp, floppy and wringable.

- Like rice, traditionally, Koreans rinse the cabbage three times. I have learnt it is much better to rinse them thoroughly, perhaps removing too much salt but this can always be remedied later. However, if you use the correct ammount of salt and don’t sprinkle excess on, three rinses are adequate. You can feel where salt residue remains as the stems are slimy and you can remove these by simply rubbing your fingers over them.

Salty kimchi will mellow with fermentation, it is probably better for it to be not salty enough than too salty, especially given the concerns over salt and blood pressure. One hint Mangchi suggests is adding some thin slices of mooli (무) if it is overly salty.

A good kimchi paste will cling to the leaves like a sauce so it is prudent to drain the segments and even wring water out and this will prevent your kimchi becoming watery as the cabbages ferment.

Plenty of recipes, online and in books, will guide you through making the paste but my all time favourite is Maangchi. Her website is enormous and her videos on Korean cooking are well presented. Here you will also find other ways to use kimchi as well as many other types of kimchi, cabbage and otherwise.

British friends who have since become lovers of kimchi often ask me how long it will keep. I tend to keep kimchi in the refrigerator in hot weather and somewhere cold, but not freezing, in winter. If you like kimchi fresh (newly made,) keeping it cool or cold will delay fermentation. If you like it sour then you can use a warm place to speed up the process. I tend to juggle things in order to better control fermentation. I made my last batch of kimchi in November and the tub in which it is stored has stood on my balcony almost 6 months. I have now moved it to the bottom of my fridge to mellow indefinitely. I have used kimchi that was over 6 months old and which had white mold on the top but this washed off and the underlying cabbage was excellent as the basis for a stew.

For my up to date and effective Kimchi recipe, check the, My Recipes, page.

©Amongst Other Things – 努江虎 – 노강호 2012 Creative Commons Licence.

Basic Kimchi Recipe (adapted for those living in the UK)

I have a number of friends and family in the UK, most notably my sister, who have been asking me to give them a kimchi recipe despite there now being many great recipes available on the Internet. So, I have written up a recipe I use when in the UK where I can’t always get authentic ingredients and I need to make substitutions.

There are many different cabbage kimchi recipes encompassing different styles to regional variations. The fact kimchi is so varied makes it exciting and without doubt, everyone who makes kimchi does so slightly different from someone else. For Koreans, when mum makes kimchi, and I’ve only met a few men who can make it, their hands invest it with love. This is the recipe I use for what is basically a straight forward kimchi comprising the basic ingredients.

Kimchi is very easy to make but it helps if you have some knowledge of how decent kimchi tastes so you are able to assess your endeavours and make adjustments to improve future attempts.

There are 9 basic ingredients:

Cabbage – Chinese leaf (called napa in the US). In the UK places like Tesco sell these but they are white, small and very stemmy. You will need 4 of these.

Mooli – once again this sometimes appear in supermarkets though they are small, skinny and bendy. Turnips, 3 0r 4 make a suitable alternative.

A whole bulb of garlic.

An inch or so of ginger. (I often omit this)

A bunch of chives or spring onions. (the type of onion Koreans use I have not seen in the UK)

Rice flour, though I have used plain flour. Not all recipes use this but I prefer paste slightly clingy)

Fish sauce – in the UK Thai Nam Pla is fine including ‘Squid’ brand.

Salt, like a whole box or packet. You will need Kosher salt or sea salt and not table salt.

Korean red pepper powder. You cannot substitute this but I have ordered it with easy in British Oriental supermarkets.

A good size plastic tub – like a Tupperware tub.

(Sugar – not all recipes use this)

Stage 1 cabbage preparation

Without any doubt the most neglected part of recipes on kimchi involve salting, and hence wilting the cabbages. All my early failures at kimchi making resulted from recipes that failed to explain this process. Getting this right is crucial but it is very simple.

1. Immerse cabbages in water. Then trim off discoloured bases, remove any bad leaves, and using a good knife begin to cut the cabbage in half from the base. Once about a third of the way into the cabbage, remove the knife and then simply tear the cabbages in half. If you have large cabbages you would in fact quarter them in this manner but if they are the small ones I’d simply half them.

Let the cabbages drain but don’t dry them.

Double check your using sea salt! Lay the cabbage half on its back, and then begin sprinkling salt on the lowest leaf, on the inside. You’ll need to raise the rest of the cabbage up to access it and at times, with a small cabbage, you can hold it in the palm of your hand and finger the leaves apart. Make sure you sprinkle salt into the base area where stems are thickest. You don’t need lots of salt, just a good pinch for each leaf. This process is finicky with small cabbages.

When all salted, put the cabbages in a bowl, throw a handful of salt over the top and then add a cup or two of water. Then simply leave them until wilted which may be between 2 hours to over night depending on the temperature. Turning them a few times during salting is useful.

How do you know when the cabbages are ready to paste? First they will have reduced in volume considerably and the container will contain a lot more water. Most importantly, the cabbages should be limp and floppy j. A good test is to wring one and it should wring just like a cloth, without tearing.

Next, rinse them 3 times. To prevent the kimchi being too salty, you can immerse cabbages in water and feel where excess salt is as it will have a slimy feel. Simply remove this with your fingers. Make sure you wash between the leaves.

Finally, wring them to remove excess water which will otherwise dilute your paste. The cabbages are now ready to paste.

Stage 2 Preparing the other ingredients.

Grate the mooli (white turnips) and squeeze any fluid from them

grate the ginger

crush the garlic

chop the spring onions (chives)

Mix 2 tablespoons of rice flour (or plain flour) in a little cold water, until it is a runny paste, then add this to a pan containing 1 and a half cups of water. Heat this until it begin to boil, stirring it constantly and adding any additional water until it resembles porridge. As it begins to boil you can add a 1 tablespoon of sugar but this is optional. The ‘porridge’ provides some body to the paste and many Koreans do not use it. Personally, I quite like a thicker paste on kimchi though not too long after fermentation, the paste will have become diluted regardless.

Stage 3 making the paste

Put the rice flour porridge in a large bowl

Add half a cup of fish sauce

3 cups of red chili powder

Add garlic, ginger, onion and mooli

Mix them all together into a paste being careful not to burn your fingers on the porridge mix.

Stage 4 pasting up the leaves

This process is almost the same as salting the leaves; lay each cabbage on its back and staring with the inside lowest leaf, paste on the mixture. Any leftover paste I simply spread over the top unless there is a lot when I might freeze it for later use. Segments should be placed in a Tupperware container with each segment being laid in a head-tail-head order. They pack better this way.

Some General Points

Where to store kimchi – basically, if it’s summer in the fridge and if winter, somewhere cold but not freezing. Kimchi ferments and as it does so the taste is altered. Part of the fun in making kimchi is in controlling the fermentation so you keep your batch in the condition in which you best enjoy it.

Fermenting kimchi – You can eat kimchi immediately. Prior and during fermentation, kimchi has a very fresh taste where individual ingredients are distinct. The kimchi will also be lively in colour. At this stage the kimchi can be salty but as fermentation and infusing continues, saltiness is lost. Some saltiness or even heat (spiciness) can be compensated with some additional sugar. If it has lost saltiness you can adjust this at this stage. Stems may still be slightly firm and thick stems may still have a little crunch left in them despite being wilted. Be prepared for some bad smells during this period. Fermentation can last up to a week depending on temperature and in comfortable room temperature (21 degrees) you can expect the lid of the Tupperware container to pop open about once every 24 hours. I’ve slept in the same room as fermenting kimchi and no longer find the aroma unpleasant but the released gasses will easily scent a room with what some will consider a very unpleasant smell.

Fermented kimchi – individual flavours are much less distinguishable, saltiness is reduced and the paste has probably thinned and increased considerably. Don’t worry; this is delicious in stews and soups. I often make minor adjustment to saltiness and sweetness.

Aged Kimchi – aged kimchi draws your mouth with its sourness and if you appreciated this type of kimchi, there is a point, which differs for each ‘connoisseur,’ where the balance of saltiness, acidity, and sweetness combine to provide an exquisite taste. I often add a little sugar or salt to this kimchi in order to balance the mixture exactly as I like it however; it never produces the same sensation as it does when the balance is naturally right. Aged kimchi is slightly yellower in colour and the stems slightly translucent. What aged kimchi might lack in lustre is compensated by its mature taste.

Once you know how you like kimchi you can move your Tupperware pot in order to slow down or suspend fermentation. After the kimchi has stopped releasing gas, it will continue to mellow but at a much slower rate and during winter months or when it is kept in a cool place or the fridge, the taste will differ very little over several months.

Very old kimchi, over six months might have mould on the surface but don’t throw it away; wash the mould of the top segments and the kimchi is still edible but much better for use in stews.

If you can obtain minari, as you can in Korea, a bunch of this, chopped can be added along with the spring onion, garlic and ginger.

Good luck and don’t be afraid to experiment as you gain experience!

© 林東哲 2011 Creative Commons Licence.

It's Alive!

Judging by the proliferation of cooking programs on British television, you might assume we are a nation which appreciates good food and enjoys cooking. Unfortunately, with the demise of many good quality butchers and fishmongers and the ascendancy of enormous supermarkets stocked full with frozen food and microwave meals, it becomes apparent that we are more interested in watching food being cooked and positively captivated if the chef is some contrived character who has enough family members in his show to almost make it a soap drama. The fact the supermarkets and brands they endorse represent the very opposite of ‘back to basic cooking,’ is rarely acknowledged.

Over my holiday, I happened to watch a program on Korean cooking which bore all the hallmarks of cooking programs which really have nothing to do with cooking and everything to do with self promotion and the establishment of a dynasty. The entire program was filmed either in the presenter’s village or in her home and introduced us to most of her family and friends.

As for the cooking, anyone acquainted with Korean cuisine knows that kimchi, a form of spicy fermented cabbage, as well as numerous other kimchi, accompany a meal. This Korean cooking was as Korean as the standard Korean pizza is Italian. Not only was there no mention of kimchi, but some very odd items were used in some standard Korean meals. I’ve both eaten and cooked bulgogi many times but this version used beetroot, asparagus and English pear. Though you can probably buy these somewhere in Korea, I’ve never seen beetroot or asparagus. As for English pear, once again this is a fruit you do not see in Korea and yet Asian pear is not difficult to buy in the UK. The program further irritated me when it was eaten off individual plates with knives and forks and in the total absence of side dishes or a plate of assorted leaves in which to wrap the bulgogi. During the entire cooking process red chili powder and red pepper paste were absent.

With so little knowledge of Korean food in the UK, especially outside London and a few other areas, it is possible for chefs to concoct any food combination and call it Korean.

Meanwhile, here is a video from my November batch of kimchi in which I opened the lid to catch the contents in the middle of a very active bout of fermentation.

I’m currently on holiday and my usual posts will re- commence next week.

© 林東哲 2011 Creative Commons Licence.

1 comment